Driven Data Poverty Prediction Challenge

For the past month, I worked on a Driven Data Competition - Predicting Poverty alongside Shadie Khubba (Yale Statistics MA '17). This post is a detailing of our results (top 10% finish ~ 200 place of 2200 contestants), code, and learnings.

The code for our best models can be found on our repo.

Motivation

Shadie and I had met in a Statistical Case Studies class that involved weekly hack sessions of solving an amorphous problem (e.g. predict New Haven real estate prices from online data). We figured this Driven Data Competition was our attempt to prove our chops in the real world and get more familiar with the Python data stack as opposed to academia's R. Plus the bragging rights and possible $ if we won.

The Problem

According to the competition website, predicting poverty from survey data is a hard problem. We were given survey response data from 3 anonymized countries (A, B & C), at both the household and individual level. Predictions were done at the household level, with each household having a 1:n relationship with individuals.

Scoring was done with a mean log loss of the three, with our predictions being offered as probabilities between 0-1 for each household being classified as poor. A baseline naive score with uniform 0.5 probability would score 0.69.

Early Learnings

We spent our first two weeks using a traditional approach; conducting exploratory data analysis and throwing some standard classifiers at the data. EDA did not prove particularly useful since each column had its data scrambled and normalized. However, two challenging issues emerged from looking at the dataset. First, the classes were imbalanced in countries B and C; the ratio of poor households to non-poor was 1:12. Second, the majority( >90%) of predictors were categorical; with several having large sets of up to 80 possible values.

We initially began throwing traditional methods at the problem: SVM, logistic regression, boosting and building off the random forest model benchmark (scored at .55).

Organizationally, we started with a GitHub repo that quickly turned into a mess. While we did organize our work with all data files/submission files saved, it quickly grew apparent that restructuring our code was inefficient. Shadie and I were working in our separate .py files, and often rewriting or re-running models locally ourselves. We didn't spend enough time planning a project structure early on; later I found out about the cookie-cutter data science project, but it was too late to implement a new project structure.

Inherent Challenges

We solved some minor problems with imbalanced classes (resampling) and missing values (imputation) but we really struggled with two major problems.

Categorical Variables

We needed a way to convert the categorical variables into numerical data such that scikit learn could actually use it as an input space. We started with one hot encoding (turning each possible value of a categorical predictor into a new 0/1 predictor), but realized it was blowing up dimensionality of the feature space, so much so that using only the continuous variables for prediction (a small fraction of the original feature space) yielded much better results (using the continuous variables and logistic regression brought us to a competitive score of 0.27, at a time when the scoreboard leaders were in the neighborhood of 0.15). Our 50 categorical variables were turning into 500 binary variables and the curse of dimensionality was taking effect: additional useless variables being added in and getting some assignment of weight. We spent time early on trying to find the right heuristics to reduce the dimensionality while not discarding potentially useful features.

Utilizing Individual Data

We began by using household data. Incorporating summary statistics (e.g. mean, range max, min) of predictions on individual data actually worsened prediction performance. Our hypothesis here is that individual predictions were offering a noisier version of what the household data already provided. Posts on the forum suggested that this was a common hurdle for the entire competitor field - many people were getting .17-.18 results by only using the household data.

CatBoost

We made a lucky breakthrough into the top 10% with a discovery of CatBoost. CatBoost is a GBM variant made by Russian search giant Yandex, and its killer feature is native support for categorical variables (hence the name categorical boosting = catboost). CatBoost is able to use statistical methods to selectively keep the most predictive values in each categorical column; saving much tedious cleaning on our end.

Our first submission here brought us in the top 8% of submissions, showing that boosting is the way to go. This dramatic improvement came solely from avoiding the curse of dimensionality and implementing a boosting algorithm (that is designed to require very little tuning)!

However, after incorporating Catboost we hit a plateau and were only able to eke out minor gains thereafter. We tried numerous feature engineering approaches for the individual data but were stumped. Our group ended up in the 200th place of over 2200 competitors though, so not a bad showing for our first time out.

Lessons Learned

We learned a lot of neat technical tricks and tools (cookiecutter, catboost, scikit learn goodies like pipeline), but the real learnings are far more generally applicable.

Try Boosting First

We spent a lot of time tossing models that didn't pan out before we arrived at the correct one. From the post-competition discussion boards, we realized that many kaggle-vets immediately tried industry standard models (XGBoost, LightBoost, CatBoost) as their first model as a matter of habit. Readings online support the idea that boosting is the go-to black box solution.

Feature Engineering is Everything

We couldn't get beyond our initial gain from using CatBoost by adding in individual data, though we tried many different approaches ranging from feature selection based off importance, predictions from individual data as features and more.

The big question was how to build features from the individual data. One of the top 3 finishers posted his feature set, and it turned out to be ridiculously simple: counting positive and negative values, the id of individuals (suggesting some ordering to household), sum of continuous values, and a count of unique categorical values.

Build a Testing Harness

A major challenge here was that we underestimated the limitations imposed by the two submissions per day. We were foolish and started off building models and then submitting to validate results. Only after many unfortunate submissions did we build out a suite of validation tools to rigorously test locally first. By the end of the first two weeks, we were running 3-fold cross validation, and eyeballing confusion matrices and predicted probability distributions. We started by treating the competition's submissions as a last validation step, not as a first one.

Next Time & Application

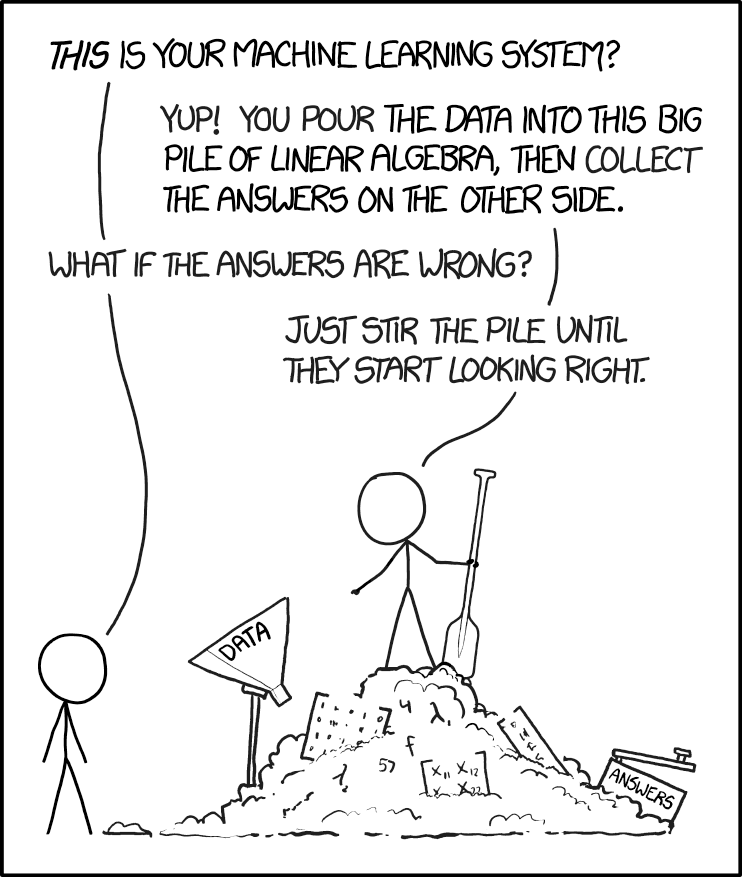

I'm optimistic that the next time we partake in a kaggle-style competition, we could place much higher if we had course corrected on these three things. Instead of scrambling to build out a testing harness with two weeks left, or furiously creating additional features in the final days, we could have comfortably spent 3 weeks feature engineering. The competition often felt like the xkcd comic below, but if we did it again, one would hope the pile of linear algebra would be less messy, and the results easier to check.

A final takeaway for both of us is that real data science life is not a kaggle-style competition. Online competitions push for a best solution; day-to-day work demands the "good enough" solution.

I'd imagine that the World Bank, which sponsored this competition, would have been equally happy to know that household data and an out of the box GBM produce a solution within 0.04 of the winning one. Putting together the $15,000 prize and paying DrivenData to run the competition shows they likely didn't know this from the get go. Clearly, some quick wins still to be found in social sector data challenges.